A Year’s Review of Fiction

One of the best seasons for reading is winter. It’s that cold, dark, and often drudging trio of months after Christmas where everyone is trying to figure out what their new year will look like and who they want to be. I read the most in winter. The chance to get cozy, make soup, and pick up a book is so alluringly coercive that I callously wish the sunlight of day away to get to blankets and furnaces in the evening. And I think I concentrate better when winter is in full swing (and it does get into gear down south. As hot as the summer is, the bitterness of a southern winter has unassuming fangs). Everything is clearer: the peaks from high mountains are much more visible, as is your field of distant views; January cuts a symbolic path to change something you’ve been meaning to about your character or trajectory; the coffee and tea taste fuller in winter, and my outings with friends feel more deeply memorable.

It’s this clarity that I want to spread out to the other months of 2024, a steady sense of being content wherever I may be, and a stronger focus as I try to keep my resolutions. There isn’t much I can do about the haze that warps the cool mountains during the summertime when I’m hiking, but I can seek more mental lucidity to help me enjoy my surroundings better. Reading oddly aids that goal. Reading fiction grandly gilds it. The virtues of the world and the realities of the people that populate it wrapped up in a neat little story have been a fantastic vessel to bring a wealth of sentiments to readers for centuries.

Maryanne Wolf, neuroscientist and author of the books Proust and the Squid and Reader, Come Home, has spent most of her professional and academic life studying the reading brain and exploring the cognitive benefits of deep reading. I’ve spent a good deal of time listening to her lectures and, though I have yet to read the former title, the latter is a tour de force that I read with alacrity in the days after the new year turned over. I found it useful to understand what the brain does when we read books, articles, posts, anything. She explains her premise by writing that “deep reading is always about connection: connecting what we know to what we read, what we read to what we feel, what we feel to what we think, and how we think to how we live out our lives in a connected world.” (163) Her focus on reading and connection charged my senses with many eureka epiphanies and silent understandings.

She has the book formatted in a series of nine letters addressed to a reader who is wondering what has happened to their ability to candidly read for hours, their wonderous aptitude to while away time stuck in Wonderland or the Shire or the fictional yet palpable world of Edith Wharton’s New York City (this last one may just be me, but I don’t know). I’ve heard from many people that the opportunities are present for a cozy night in with a book but have found their attention lacking to such a degree that it ruins that opportunity, and the time goes wasted for a screen.

Wolf doesn’t expound on any tribulations that digital media and screens bring to society; it isn’t that kind of approach. What she does is highlight how digital media can be better integrated into up-and-coming lives without it being outright tyrannical, cementing a permanent distraction system in our lives. Her research and exposition also lay in what we can see clearly now: that our world, should we not take hold and get a firmer grasp on the technological forces in our lives, will lead to further artificial shortness of details, information overload, diminishing cognitive patience, a lack of critical analysis, and, most important to me, a deprivation of joy and empathy in the world.

But. Books offer every generation a beckoning solace, should their demands be met, that Wolf articulates in the most joyful terms. Books allow us the breadth and the time to crawl into the shoes of a character and walk with them through their story, often through unnoticeable processes. They can, if we let them, indicate different angles and points of view that we might never have considered. Their physicality calms all the disparate stimuli floating around us and convenes the eyes down to the single page before us, opening the space to underline, make notes, and go back and forth across the sentences, just in case we missed something. In the interviews Wolf gives, the joy of bringing an understanding to how deep reading affects the brain is overflowing in her voice as she passionately relays her research and convictions. Her life’s mission, to see literacy across the globe and to have literacy be internalized as a fundamental human right, is truly extraordinary.

I don’t know where we’d be without the sanctity of the written word enclosed between two tangible covers, someone’s world bound in a snapshot that a post on Instagram, with all its lovely contours and saturation, can’t quite capture entirely. It’s our imagination muscle that flexes in both fiction and non-fiction. I remember reading Lord of the Rings for the first time, traversing the maps of Middle Earth, and feeling an exuberant glee once the forces of good started to reverse the course of evil. I recall finishing A Little Life (as do my friends because they all worried about me) and being depressed over it for an entire month. Sitting down with The Age of Innocence led me to my favorite classical storyteller of all time. And I reminisce about being read to as a child all the stories that connected me to my parents as they brought a book to life with different voices for each silly character.

I give a lot of telling, not showing, in enticing you to pick up Reader, Come Home, I understand. I’ve gushed a lot over the simple idea of books as well. But it’s essential not just to me but an entire camaraderie that our complicated lives aren’t done justice by condensing everything down to an overstimulated piece of television or pruning important details to squeeze into a three-paragraph blog post. Those two mediums are providential to our entertainment as well, but the certainty of a book is that it requires work to get to the raw marrow, not just a surface-level understanding.

As I mentioned, I read the most books in winter. My focus is sharper, and my capacity to get wrapped and twisted up by a story is never as keen. Yes, it’s surprising that a place apart from the trees can provide such a perfect environment, awkwardly sitting on the tile of the first-floor bathroom, back pressed into the corner of the walls, while the heat of the nearby furnace blows out from the vent with such force that when I open the door to go to bed, the colder air of the rest of the house blows in like snow. It’s a position I relish to be in all year long. If you can’t climb the mountains outside, climb them in books.

⌈⌊⌉⌋

Stoner

John Williams

What a privilege it was to read this classic so early in the year, and oh my, how much more depressing could it have been? It is depressing, but let me get to why it’s one of the six I loved best this year:

This is the vivid and softly devasting tale of William Stoner, a Midwesterner who, in 1910, is sent from his parents’ poor working farm to attend the new University of Missouri where he is to obtain a degree in Agriculture. New interests are piqued, though, when Archer Sloane, the professor of his English requirement, nudges him toward a degree in letters and, thus, forges a new path not in farming but academics. The novel carries us through the entirety of Stoner’s life, all the way up until his death at the end, his last slip into obscurity.

Because that’s what this novel is: a character who works his entire life, makes a few blunders and mistakes, bears the brutish route of his life, and dies a relatively dim death. I don’t mean to make it sound boring because it isn’t. There’s drama and tension and emotion and unfulfilled ends and unreciprocated love. The narrative spans a lifetime in just a few short pages, and once your time is complete with it, you clutch the book to your chest, knowing that at least you’ve borne witness to this fictional character’s life and the fictional things he accomplished.

I loved this book because of its nuanced messages on what legacy is. Stoner lives his life unconcerned with how or what he’ll be remembered by. Is it not enough to do just as much? Most people live quiet and untouchable lives the world over and triumph in the face of deep personal struggle and trauma without anyone else ever knowing it. They work hard and accept things as they come. It’s a very midwestern approach, but if you’re ill of reading predictable classics, I bet this one hasn’t crossed your radar until now.

⌈⌊⌉⌋

The Songbook of Benny Lament

Amy Harmon

Hold on to your butts because this story uncompromisingly weaves through four-hundred-pages of one of the loveliest books I’ve had the fortune to find. Harmon envelopes tragedy, romance, shadowy crime plots, the mob, and the undulations of 1960s culture and society in such a way that the setting in and of itself becomes a character.

Against this setting is Benny Lament, a star songwriter and pianist whose father, Jack, coaxes him into attending a nightclub to see a band called Minefield, a band Jack wholeheartedly encourages Benny to become a part of since he possesses many contacts in the music industry. The petite powerhouse lead singer is a black woman named Ester Mine who, together with her brothers, manages a tight contract with the nightclub and with whom Benny becomes instantly enamored (he just doesn’t realize it yet).

Through a series of encounters, propositions, and blunders, Benny convinces Ester (and himself) to record a couple of singles and put them out to the public to see what comes of it. And the public loves it skyrocketing Minefield, Ester, and Benny increasingly into the limelight, the show relying on the silly banter between Benny and Ester as much as Benny’s piano and Ester’s voice. All the while, Benny is escaping the sinister realities of his life and who his family is: mobsters keep close eyes on him, reporting back to his uncle, Salvatore Vitale. Backstory reveals a ruthless person in Sal Vitale that not only fuels Benny’s need to outrun his family but also keeps him on his toes the entire time. When Ester becomes involved, who she is, and who she’s connected to, everything becomes much more entangled. So, while the band is out recording with Berry Gordy and traveling the Northeast, many menacing affairs lurk just in the darkness of a musician’s success and life.

This story is sublime. Its pacing is excellent, the structure is unique and thought out (shifting between short radio interview segments that Benny is telling in the present leading into the flashbacks of the story he remembers years prior), and it’s hard to categorize. The savoriness of the suspense and the sweetness of the romance combine to create a story that I feel would make an excellent musical adaption if not a movie.

⌈⌊⌉⌋

These Silent Woods

Kimi Cunningham-Grant

I didn’t even read a synopsis of this book when I purchased it. I just saw the title set against dark, subdued pine trees on the cover, where the only bright detail is a red cabin in a clearing set amongst modest mountains. I was instantly hooked by its presence and thought of no conceivable way this book could be bad.

Sure enough, I was right.

Cooper (Kenny) and Finch (Grace Elizabeth) are father and daughter living in a remote cabin somewhere in the northern Appalachians. Their lives are self-sustaining, their solitude essential, and their entire existence relies solely on being undetectable. There are no neighbors save for Scotland, a thorny character who always leaves Cooper feeling uneasy and threatened, but he’s good to Finch, teaching her the ways of the woods. These establishing facts leave troubling feelings in the reader as well.

Once a year, Cooper’s friend Jake, someone he met while in the forces serving three tours in Afghanistan, trundles up the mountain to deliver annual groceries and supplies to Cooper and Finch. They don’t go down into town in fear of happening upon someone they know or who might know them. But this year, emergency surrounds the pair when Jake doesn’t show up. We don’t know what Cooper is trying to hide or why he’s wiped his and Finch’s existence from the world, but we do know it’s a secret he finds necessary to maintain in order to keep his life. And now it’s compromised.

In having to contend with how they will get supplies for the upcoming year, another issue presents itself. A hiker is out one day while the duo is in their hunting stand. She pulls out a camera to take pictures of the surrounding scenery and, in the process, unknowingly captures a picture of Cooper and Finch. Eight years of living solely on their own with only a single friend knowing where they are (and who has missed the date he was supposed to show up) leaves Cooper panicking. What will happen to them if they’re found? Are the stories of Cooper’s past forgotten? Are the people who were out to get him still on the hunt?

This book is the right blend of mystery and literary fiction, with sufficiently developed characters along the way, revealing more and more of what Cooper ran from. It’s bittersweet and softly tragic, but the ending, tenderly blind-sighted as I was by it, makes this book worth reading. The pacing is a little Hallmark-movie quick, but its gracious message and characters with bottomless self-doubt will have you rooting for their peace of mind the further you read.

I look forward to seeing more from this author.

⌈⌊⌉⌋

Summer

Edith Wharton

A girl exits the red house of Lawyer Royall in the small New England town of North Dormer, a town of only a single street where the wealthiest residents couldn’t hold a candle to rich Manhattanites. She goes to fulfill her shift at the town library run by Mrs. Hattchard. A young man by the name of Lucius Harney enters the dusty building and claims to be in North Dormer to research local architecture. And the sixteen-year-old Charity Royall, the girl in frame, embarks upon a fairytale romance that spurs an unforeseen joy, fulfillment, and love before that life is flipped upside down by happenstance.

This is the novel Edith Wharton proclaimed to be one of her greatest masterpieces which makes me wonder why I never read it in school, why I hadn’t heard of it ever. It’s different from her other novels; most notable is that it doesn’t take place in New York City or Europe, but it carries that same pleasantly wounding quality that colors all her stories and characters. And this one is no less unfortunate than, say, The House of Mirth or The Age of Innocence. It appears more candid in its solicitations and rawer in its storytelling, more honest of what becomes of poor Charity, who was brought down as a child from the mountain that looms above North Dormer, where she is raised by Lawyer Royall, a despicable man who raises her on falsely savage stories of where she comes from.

Lucius Harney is the escape from her life, an endeavor she definitely wants to start. He opens the world to her, one she does not know, and ushers her into a more knowledgeable existence. Unfortunately, it does not last, and Harney reveals the shallowness and spinelessness of his demeanor, leaving poor Charity to nurse her broken present and begrudge her broken future.

I did like this book despite how depressing it is and how I’m making it sound. All of the Wharton traits are here: language and syntax as rich as buttercream, a somber yet satiating arch of a story, and characters developed to just the right degree so the reader is perplexed by them. It’s melancholic how Charity, so independent and strong and hopeful and preparing to fend for herself so she doesn’t have to bank on others (especially those in her immediate vicinity), gets caught up in the spectacle of Lucius Harney, falling for him. Her dream is a crystal glass, and he is a hammer.

⌈⌊⌉⌋

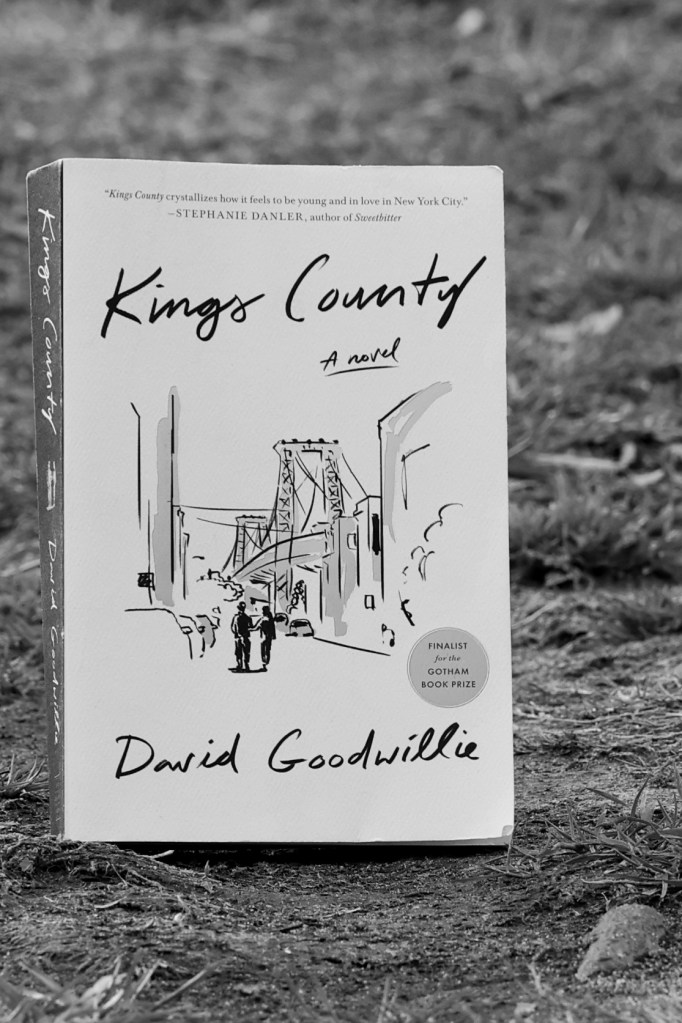

Kings County

David Goodwillie

Several echoed the best description of this read in almost every review I consumed: “I wasn’t invested in this book until I was invested in this book.” Goodwillie cooked up a massive slow-burn of a novel; once the snowball hits a point on the mountain slope, it is impossible to put a stop to it. This book is incredible…as long as you stick with it.

Like another book on this list, I bought this solely because of the simple art on the cover and the fact that it’s in New York. I love New York novels (see Edith Wharton), and though New Yorkers may be the better judge of whether this is a good New York novel, the city as the backdrop makes this story even more charmingly atmospheric.

Audrey and Theo are two unlikely people to fall madly in love: Theo is a flailing literary scout who possesses more good-hearted nature in his awkwardness than any character I’ve read in the past year, and Audrey is a successful band scout, expertly flowing about the industry, not taking crap from anyone, and enjoying her artistic life in Brooklyn. The novel starts with an after-party for a band Audrey is representing. Theo arrives late in the evening, and amid the party’s glow, the band’s manager, a sweaty and cumbersome dude named Lucas, is busily talking on his phone, asking about some guy named Fender. Audrey picks up on this and inquires. Fender, a friend Audrey had when she first moved to the city, has disappeared and has potentially committed suicide. Audrey and Theo leave in a flurry of anxiety, and Theo’s confusion towards Audrey’s sudden shift in temperament summons a wedge that starts growing between them.

Through a series of flashbacks and interactions in the present day, we see the trajectory of Audrey’s life moving from Florida to Brooklyn, the course of Theo’s life as he tries to find himself in the midst of expectations and personal handicaps, the circumstances surrounding their friends, and what became of Fender. Though it takes some effort to read through the details of these two lives, it starts to cohesively combust as Audrey and Theo’s relationship pulls and strains for the first time. Dark pasts come out to play again, and personal barriers prevent real and honest vulnerability. When you begin Kings County, you start a fire.

⌈⌊⌉⌋

The Murder of Mr. Wickham

Claudia Gray

Perhaps many would agree that Jane Austen is a standard the world could enjoy more of, and something that will liven the hearts of Austen and mystery fans culminates in this title. It is as if Austen herself wrote this murder mystery: from the funny witticisms to the drama of rich people partying in each other’s houses, Gray has hatched an excellent serial idea that I’m surprised hadn’t been captured as clearly by anyone sooner.

Set twenty years after the events of Pride and Prejudice (of which I had the liberty and freedom to read once more this past year), Jonathan and Emma Knightley intend to host a summer party at their estate, to which their friends from all the neighboring counties are invited. The Darcys, the Brandons, the Bertrams, and the Wentworths all attend, but one guest makes his uninvited appearance, much to everyone’s surprise, dismay, and annoyance.

Mr. Wickham, of P&P infamy, has spent the last couple of years as a swindler, a shadowy figure that has negatively affected every family’s life, and he shows up at Donwell Abbey. Everyone’s ease is put off, but they try to accommodate with their best regency manners as possible. Our two protagonists, Jonathan Darcy and Juliet Tilney, son of Fitzwilliam and Lizzy Darcy and daughter of Catherine and Henry Tilney, respectively, notice this shift in everyone’s mood.

Both have come on holiday to the Knightley’s party and find themselves in peculiar circumstances when one stormy night, lightning flashing in the deeply shadowed halls, produces a dead Mr. Wickham.

Juliet herself discovers him, and an investigation opens. The assumption that it was a servant or some sort of gypsy intruder circulates, and Juliet refuses to let an unknown innocent go to the gallows. It must’ve been a guest of Donwell, and she recruits Johnathan, a loner of sorts—a trait Lizzy and Mr. Darcy wish didn’t befall their son—to help her investigate. Together, they lead a covert investigation while maintaining their decorum and general agreeableness.

It is a winding country road of a novel. It’s paced eloquently and consistently and without an overbearing tone of suspense. At the end of nearly every lengthy chapter, Gray includes a small, peculiar detail that propels the reader into the next chapter even though it’s way past bedtime. And it is so properly themed: Austen’s words find themselves conveniently placed to the point that I wish she had written it. It involves all of our favorite Austen characters, all a bit older and strangely disheveled because, as we find out, they all have something to hide, they all have something they don’t want to get out, and all of them are suspects.

⌈⌊⌉⌋

Speaking of resolutions, I know you’ve got some! Why not add another? Just one novel can begin one of the worthiest journeys you’ll ever take, and you won’t ever be alone again. Start by making it a game and do what I do: take a book by the last page, read the ending paragraphs, and if they stir even the slightest wonder, check it out. Purchase it. Borrow it. See how those ending paragraphs came to be. This method, surprisingly, hasn’t produced a bad book for me yet. Go climb those mountains.

⌈⌊⌉⌋

Eric Whitacre — The Seal Lullaby

Story Untold — What If

Dreamwake — Memories

Fay Wildhagen — Coming Home

Coldplay — A Message

Woodlock — The Garden

New Constellations — Think it Over